A realistic pathway for the world’s transition away from coal has been presented by University of Queensland researchers who identified contradictions and constraints in 118 nations’ efforts, country by country. Here, Dr Kamila Svobodova argues that while countries like the United States, China, Russia and Australia have a responsibility to lead effective change, it is more likely countries such as Germany, Canada and Iran will.

Demand for global climate change action is at its peak, but the acceptance of radical emission reduction strategies is not pervasive. Such a strategy relies on a rapid and unprecedented global-scale solution, and an active cooperation or leadership of a handful of countries.

These countries, including Australia, have the responsibility and capacity to carry the world through a transition period. However, they face major uncertainties in targeting global versus national interests, following a continuous increase in their energy consumption.

Is Australia’s lagging position in energy transition unalterable? Definitely not, but a realistic strategy for international emissions reduction must recognise that the constraints and contradictions within the current Australian context are unlikely to be overcome in the near future. These constraints are also present in other countries.

In our paper Complexities and contradictions in the global energy transition: A re-evaluation of country-level factors and dependencies, we expanded the literature on coal phase-out by designing a multi-level assessment framework. Based on country-level capacity, ability and urgency to transit, the framework examines the potential of 118 state nations to phase out coal and their roles in the global energy transition.

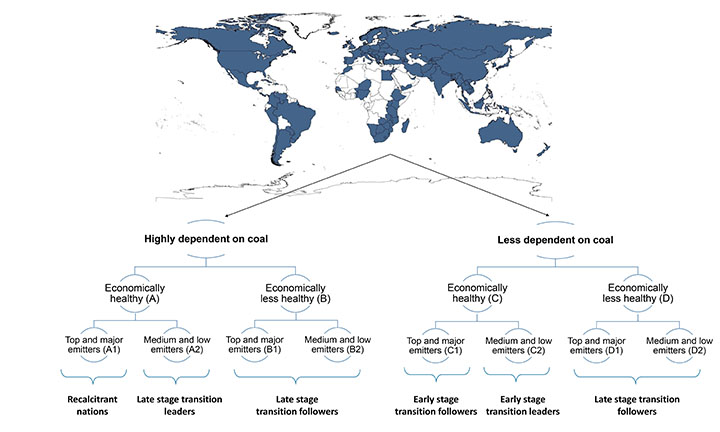

Based on their economic health and dependency on coal, the framework divides countries into four groups labelled A-D, and then refines these groups by analysing each countries’ carbon contribution. Identifying countries with similar conditions provides a picture of global transition capacity, which can reveal potential roles, path direction and speed of change.

As I hinted earlier, Australia currently finds itself alongside what the study identifies as the “Recalcitrant Nations” (Group A1). These countries are economically healthy, highly dependent on coal and are top or major emitters. Since human and economic development in these countries is high, they are all capable and, more importantly, responsible for leading the transition from coal to renewables. China, the United States of America, Russia and Japan join Australia in this group. As you will see, while these countries differ in their economic structures and energy dependencies, their approach to a coal phase-out is remarkably similar.

Before I examine those countries, I will talk about Australia’s coal phase-out efforts. Apart from the nationally stated Renewable Energy Target, which will expire in 2020 with no replacement revealed yet, the Federal Government has tabled no policy to move the phase-out of coal beyond the domain of market forces.

The Australian Energy Market Operator’s modelling, which suggests two-thirds of coal-fired energy will be out of the system by 2040, does not alter this. Only a more rapid scenario would be compatible with the global two-degree scenario.

In a choice between imperfect alternatives, the Australian government appears to be gravitating towards maintaining a cautious balance of market protectionism with a façade of supporting incremental investments in cleaner energy alternatives.

The United States also has no federal plan to phase-out coal in power generation. In fact, the current administration has vowed to revive the coal industry and kick-started this by moving to repeal the previous administration’s Clean Power Plan. In line with other recalcitrant nations, the United States has not declared a 2050 target for renewable energy.

Two years ago, the Federal Government even introduced tariffs on the import of solar panels that led renewable energy companies to freeze or cancel investments of US$2.5 billion.

Similarly, in Russia, there is no public agenda for phasing out coal. Like the United States, Russia has focused on strengthening its own energy security, through policies that encourage the development of renewables that only marginally increase their share in the national electricity mix. In fact, the Russian government aims to increase the share of coal in electricity generation from 16 per cent to 17 per cent by 2035.

China can be seen as a pivotal nation in the post-Paris era due to its population and global economic ambitions. The Chinese government has no public phase-out plans for coal but has stated its intent to reduce the share of the country’s overall energy mix from 64 per cent in 2019 to 58 per cent by 2020.

This move reflects the urgency with which action is needed. Some other efforts have also had an impact, such as strict requirements for the construction of new coal power plants, the country’s 2018-2020 Air Pollution Plan, or the allocation of 30 billion yuan (US$4.56 billion) to support coal mining regions in their transition from coal economies.

One can assume that if the country makes significant progress in phasing out its dependency on coal, the key measures on economic health and energy mix would happen at an incremental pace.

Clearly, Australia belongs to this recalcitrant group. But does it have to be? Probably not. Given Australia’s unique context, policymakers could try to push the country into another group, such as the “Early Stage Transition Followers”, accompanied by countries such as Germany, the Netherlands or the UK.

Germany, which is frequently identified as a frontrunner in the transition to renewable energy, is a prime example of why any realistic phase-out plan would need to be long running, complex and account for national differences beyond carbon contribution.

Although Germany’s carbon footprint may not be as small or as quickly decreasing as some Scandinavian countries from the “Early Stage Transition Leaders” group, it remains the only major industrial economy that has steadily decreased its reliance on fossil fuels.

This success is the result of a two-phased transition. The country pushed ahead with its now much-duplicated feed-in tariff system, which enabled citizens, municipalities and cooperatives to participate in the energy transition. This led to more than 40 per cent of the country’s clean power-producing facilities being owned by citizens, farmers and cooperatives.

The second transition phase focuses on managing the increasing renewables inventory while controlling cost and access across the system.

Could Australia adopt a similar approach to Germany? It is unlikely. Germany and Australia have different types of economies and energy dependencies, and a very different political and industrial culture. As the largest manufacturing economy in Europe, Germany’s coal is primarily used in energy production. Australia’s coal economy is driven by exports.

Furthermore, cultural differences, especially regarding climate change, are evident. Germany has a long-lasting good relationship between trade unions, miners and states. This brings trust for future transition plans. A fundamental part of Germany’s successful initiative is the wide-ranging climate change consensus. More than 90 per cent of German citizens support an expedited approach to energy transition. This level of popular consensus is atypical in modern democracies. Germany’s major political parties all largely agreed on the same phase-out strategy. Neither of these things can be seen in Australia.

A realistic coal phase out plan for Australia must be different, driven by different strategies but similarly as in Germany, built on long-lasting trust and understanding among key players.